America used to be a great country where if you were on Medicaid and had a low income, you could buy 240 oxycodone pills for a dollar and sell them for up to 4000 dollars. Sadly, this could lead to overdose deaths.

Angus Deaton writes in the Boston Review

The United States has seen an epidemic of what Case and I have called “deaths of despair”—

though they may have been no such thing. The fact is recreational drug use tends to be....urm... recreational rather than gloomy and despairing.

deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease.

Suicide may be contrary to Judaeo-Christian ethics. But there are 'honour' or 'shame' societies where it considered a sign of innate nobility.

These deaths, all of which are to a great extent self-inflicted, are seen in few other rich countries, but in none, except in Scotland,

which is more similar to Scandinavia in that there is strong support for a full fledged cradle to grave welfare state.

do we see anything like the scale of the tragedy that is being experienced in America.

There is a stereotype of a certain class of Scottish people as drinking too much and eating only deep fried Mars bars. Is Deaton saying working class Americans are like working class Scottish people? That still makes them way cooler than the people of most other nations.

Elevated adult mortality rates are often a measure of societal failure,

or of not being a boring sod

especially so when those deaths come not from an infectious disease, like COVID-19, or from a failing health system, but from personal affliction.

You say affliction, I say living my best life rather than being a granola eating pussy.

As Emile Durkheim argued long ago, suicide, which is the archetypal self-inflicted destruction, is more likely to happen during times of intolerable social change when people have lost the relationships with others and the social framework that they need to support their flourishing.

Durkheim lived at a time when some people in great Western Cities were literally dying of starvation. There was no social safety net for 'self-respecting' people.

Which suggests that despair actually means having partied a lot. It may be that Deaton is a stern Christian moralist who says- 'you think looking at dirty pictures and having a crafty wank is a good way to pass the time. You are wrong. You are clinically depressed because your soul is atrophying. You are headed to Hell and in your heart of hearts, you know this very well. You can fool others that you are having a good time, but you are actually deeply unhappy.'

It may be that we could benefit by heeding such advise. The Puritan work ethic can make families and nations rich. But, it must be admitted, they become as boring as shit.

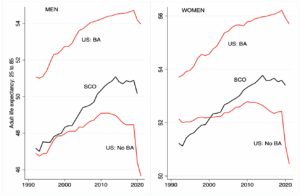

Figure 1 shows trends in life expectancy for men and women in the United States, in the UK, and in Scotland from 1980 to 2019. Upward trends are good and dominate the picture. The increases are more rapid for men than for women: women are less likely to die of heart attacks than are men, and so have benefited less from the decline in heart disease that had long been a leading cause of falling mortality. Scotland does worse than the UK, and is more like the United States, though Scots women do worse than American women; a history of heavy smoking does much to explain these Scottish outcomes.

Most of us started smoking not because we despaired of life but because we thought it made us look cool.

If we focus on the years just before the pandemic, we see a slowdown in progress in all three countries; this is happening in several other rich countries, though not all. We see signs of falling life expectancy even before the pandemic. (I do not discuss the pandemic here because it raises issues beyond my main argument.) Falling life expectancy is something that rich countries have long been used to not happening.

Figure 2: Adult life expectancy in Scotland and the United States (Source: U.S. Vital Statistics and Scottish life tables)

Figure 2 shows life expectancy at twenty-five and, for the United States, divides the data into those with and without a four-year college degree.

Which probably corresponds to a distinctions between boring people who do their homework and kids who love to party.

In Scotland, we do not (yet) have the data to make the split. The remarkable thing here is that, in the United States, those without a B.A. have experienced falling (adult) life expectancy since 2010, while those with the degree have continued to see improvements.

People who can sit through boring lectures may also be the type who give up smoking and take up eating granola.

Adult mortality rates are going in opposite directions for the more and less educated.

Because it is easier to get into College and to stay there and get a worthless degree which however is positively correlated to doing boring shit rather than partying hearty.

The gap, which was about 2.5 years in 1992, doubled to 5 years in 2019 and reached 7 years in 2021. Whatever plague is afflicting the United States, a bachelor’s degree is an effective antidote.

Nope. Being a boring sod is the secret of living a long boring life.

The Scots look more like the less-educated Americans, though they do a little better, but note again that we cannot split the Scottish data by educational attainment.

Even higher education can't turn a true Scotsman into a boring cunt.

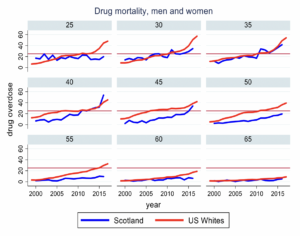

Figure 3: Drug overdose deaths, by age group, in the United States and Scotland (Source: U.S. Vital Statistics and WHO mortality database)

Figure 3 presents trends in overdose deaths by age groups. U.S. whites are shown in red, and Scots in blue. Scotland is not as bad as the United States, but it is close, especially in the midlife age groups. No other country in the rich world looks like this.

Angus is Scottish. Is he boasting about how cool the Scots are?

In America, there is a narrative of overworked blue collar and self-employed people suffering pain and having to take recourse to over-priced opioids. But Scotland has the NHS and strong Trade Unions and pretty decent employers.

In 1995 the painkiller OxyContin, manufactured by Purdue Pharmaceutical, a private company owned by the Sackler family, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). OxyContin is an opioid; think of it as a half-strength dose of heroin in pill form with an FDA label of approval—effective for pain relief, and highly addictive. Traditionally, doctors in the United States did not prescribe opiates, even for terminally ill cancer patients—unlike in Britain—but they were persuaded by relentless marketing campaigns and a good deal of misdirection that OxyContin was safe for chronic pain. Chronic pain had been on the rise in the United States for some time, and Purdue and their distributors targeted communities where pain was prevalent: a typical example is a company coal town in West Virginia where the company and the coal had recently vanished. Overdose deaths began to rise soon afterwards. By 2012 enough opioid prescriptions were being written for every American adult to have a month’s supply. In time, physicians began to realize what they had done and cut back on prescriptions. Or at least most did; a few turned themselves into drug dealers and operated pill mills, selling pills for money or, in some cases, for sex. Many of those doctors are now in jail. (Barbara Kingsolver’s recent Demon Copperhead, set in southwest Virginia, is a fictionalized account of the social devastation, especially among children and young people.)

So this is a story about Doctors who turned into drug pushers so as to buy sportscars. The good news is that some people are in jail. Still, the fact that Scotland too has a drug problem- illegal drugs that is- suggests that a lot of usage was recreational. People did know that pain management via drugs was risky just as taking sleeping draughts to sleep is likely to send you round the twist.

Smith’s notion of the “invisible hand,” the idea that self-interest and competition will often work to the general good, is what economists today call the first welfare theorem.

The invisible hand will get you better quality and price and convenience for whatever poison you want. It is a separate matter that Society can outlaw repugnant markets and severely punish any who deal in them.

Exactly what this general good is and exactly how it gets promoted have been central topics in economics ever since. The work of Gerard Debreu and Kenneth Arrow in the 1950s

was useless because it ignored Knightian Uncertainty. An Arrow-Debreu universe is one where there is no need for language or education or any sort of coordination mechanism.

eventually provided a comprehensive analysis of Smith’s insight, including precise definitions of what sort of general good gets promoted,

Nonsense! The thing was 'anything goes'.

what, if any, are the limitations to that goodness, and what conditions must hold for the process to work.

The condition was no Knightian Uncertainty i.e. all future states of the world are probabilistically known.

I want to discuss two issues. First, there is the question of whose good we are talking about. The butcher, at least qua butcher, cares not at all about social justice; to her, money is money, and it doesn’t matter whose it is.

No. The butcher may only want to sell to fellow Christians or Jews or whatever. The law may prevent him from discriminating in this way.

The good that markets promote is the goodness of efficiency—the elimination of waste,

No. If markets clear, all that happens is that nobody can't buy or sell at the going price.

in the sense that it is impossible to make anyone better off without hurting at least one other person.

No. This can always happen because relevant information is not available. I may have on my bookshelf a book which would be very valuable to you because it is actually by your biological mother. But you don't know this and I don't know this and so a potential Pareto improvement is not attained.

Certainly that is a good thing, but it is not the same thing as the goodness of justice.

If we received justice who would escape whipping?

The theorem says nothing about poverty nor about the distribution of income.

The theorem says nothing, period. If everybody has perfect information, they also have perfect information about what they need to do every day. There is no need for any money to change hands or actual markets to exist. Everybody would be a 'windowless monad' in 'pre-established harmony'.

It is possible that the poor gain through markets

Not if they are really poor. Then they starve to death.

—possibly by more than the rich, as was argued by Mises, Hayek, and others—but that is a different matter, requiring separate theoretical or empirical demonstration.

No. The poor will kill you if you start doing any fucking empirical demonstrations on them. The rich may just instruct their butlers to kick you in the seat of the pants and tell you to fuck the fuck off.

A second condition is good information: that people know about the meat, beer, and bread that they are buying, and that they understand what will happen when they consume it.

Which is why new products should never be put on the market.

Arrow understood that information is always imperfect, but that the imperfection is more of a problem in some markets than others: not so much in meat, beer, and bread, for example,

Fuck off! Eat bad meat and you get the shits.

but a crippling problem in the provision of health care.

You are already seriously fucked if you are having to see a Doctor. This is no the case when you buy a beer or a burger.

Patients must rely on physicians to tell them what they need in a way that is not true of the butcher, who does not expect to be obeyed when she tells you that, just to be sure you have enough, you should take home the carcass hanging in her shop.

Shit like that may happen to Deaton, it doesn't happen to me. I may be fat but I don't look like I could eat a whole cow.

In the light of this fact, Arrow concluded that private markets should not be used to provide health care.

If there hadn't been private markets for medicine there couldn't have been a public health system. The latter can just as easily turn to shit as the former.

“It is the general social consensus, clearly, that the laissez-faire solution for medicine is intolerable,” he wrote.

But the medical profession, like the accountancy or actuarial or engineering professions, can set up a professional body and a certification process and a professional indemnity fund and so forth. But any manufacturing industry can do something similar. This is like the 'market for lemons'.

This is (at least one of the) reason(s) why almost all wealthy countries do not rely on pure laissez-faire to provide health care.

No. The reason is because voters- especially older voters- want taxpayers to pay to keep them alive.

So why is America different?

It is very big. It is multi-ethnic. Also, at a time when the labour market was tighter, employers wanted to tie employees to them (this is like 'efficiency wages') through superior medical coverage.

And what does America’s failure to heed Arrow

Arrow wasn't raising red flags about opioid abuse

have to do with the Sacklers, or with deaths of despair, or with OxyContin and the pain and despair that it exploited and created?

Nothing at all. I suppose, the truth is, America legalized a type of drug and made some tax revenue out of it before handing the drug trade to the sweet and reasonable dudes who run the cartels.

There are many reasons why America’s health care system is not like the Canadian or European systems, including, perhaps most importantly, the legacy of racial injustice.

Germany was never guilty of 'racial injustice'.

But today I want to focus on economics.

Neither America nor American economics was always committed to laissez-faire.

It was committed to exterminating the First Nations and using African slave labour. Deaton thinks the place was a Socialist commune committed to vegetarianism and abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and mind altering substances.

In 1886, in his draft of the founding principles of the American Economic Association, Richard Ely

a White Supremacist who described African Americans as 'shiftless and ignorant.'

wrote that “the doctrine of laissez-faire is unsafe in politics and unsound in morals.”

Also Black peeps have ginormous dongs. We must string them up before they corrupt White women buy giving them orgasms.

The Association’s subscribers knew something about morals;

and the danger of ginormous Black dongs. To be fair, Ely and, his student, Ross who coined the term 'race suicide', also hated Catholics and Jews and Socialists and so forth.

in his 2021 book Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, Ben Friedman notes that 23 of its original 181 members were Protestant clergymen.

Which is why they hated Catholics.

The shift began with Chicago economics, and the strange transformation of Smith’s economics into Chicago economics (which, as the story of Stigler’s quip attests, was branded as Smithian economics). Liu’s book is a splendid history of how this happened.

Chicago economists did not argue that markets could not fail—just that any attempt to address market failures would only make things worse.

Because those addressing the market failure were actually only interested in capturing a rent for themselves. If Capitalists are greedy so are those who claim to be able to tame those savage beasts.

As Angus Burgin has finely documented in The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression (2015), Chicago economists did not argue that Arrow’s theorems were wrong, nor that markets could not fail—just that any attempt to address market failures would only make things worse. Worse still was the potential loss of freedom that, from a libertarian perspective, would follow from attempts to interfere with free markets.

Better King Log than King Stork.

Chicago economics is important. Many of us were brought up on a naïve economics in which market failures could be fixed by government action; indeed, that was one of government’s main functions. Chicago economists correctly argued that governments could fail, too. Stigler himself argued that regulation was often undone because regulators were captured by those they were supposed to be regulating. Monopolies, according to Milton Friedman, were usually temporary and were more likely to be competed away than reformed; markets were more likely to correct themselves than to be corrected by government regulators. James Buchanan argued that politicians, like consumers and producers, had interests of their own, so that the government cannot be assumed to act in the public interest and often does not. Friedman argued in favor of tax shelters because they put brakes on government expenditures. Inequality was not a problem in need of a solution. In fact, he argued, most inequality was just: the thrifty got rich and spendthrifts got poor, so redistribution through taxation penalized virtue and subsidized the spendthrift. Friedman believed that attempts to limit inequality of outcomes would stifle freedom, that “equality comes sharply into conflict with freedom; one must choose,” but, in the end, choosing equality would result in less of it. Free markets, on the other hand, would produce both freedom and equality. These ideas were often grounded more in hope than in reality, and history abounds with examples of the opposite: indeed, the early conflict between Jefferson and Hamilton concerned the former’s horror over speculation by unregulated bankers.

The fact is economists were merely playing catch up with what drunken businessmen were saying to each other.

Gary Becker extended the range of Chicago economics beyond its traditional subject matter. He applied the standard apparatus of consumer choice to topics in health, sociology, law, and political science. On addiction, he argued that people dabbling in drugs recognize the dangers and will take them into account. If someone uses fentanyl, they know that subsequent use will generate less pleasure than earlier use, that in the end, it might be impossible to stop, and that their life might end in a hell of addiction. They know all this, but are rational, and so will only use if the net benefit is positive. There is no need to regulate, Becker believed: trying to stop drug use will only cause unnecessary harm and hurt those who are rationally consuming them.

What Becker believed did not matter. What rock stars believed did. People want to be cool like rockstars. They don't give a crap about what economists think of their behaviour. The fact is, drug and alcohol use is a 'costly signal'. If you can be high functioning when off your head on drink or drugs, you are a winner. Women want to be with you. Men want to be you or, in you- if they are that way inclined.

Chicago analysis serves as an important corrective to the naïve view that the business of government is to correct market failures. But it all went too far, and morphed into a belief that government was entirely incapable of helping its citizens. In a recent podcast, economist Jim Heckman tells that when he was a young economist at Chicago, he wrote about the effects of civil rights laws in the 1960s on the wages of Black people in South Carolina. The resulting paper, published in 1989 in the American Economic Review, is the one of which Heckman is most proud. But his colleagues were appalled. Stigler and D. Gale Johnson, then chair of the economics department, simply would not have it. “Do you really believe that the government did good?” they asked him. This was not a topic that could possibly be subject to empirical inquiry; it had been established that the government could do nothing to help.

The point of this anecdote is not that Chicago economists were shitty but that all economists are at least twenty years behind the times. In 1989, America was intervening to put an end to apartheid in South Africa. It wasn't planning on restoring Jim Crow.

If the government could do nothing for African Americans,

It was killing or incarcerating them. That wasn't, it isn't, a good use of tax money. I suppose, Deaton means the Federal Government which was less horrible than the local Sheriff in a Southern Town.

then it certainly could do nothing to improve the delivery of health care.

That might literally be true, from the legal point of view.

Price controls were anathema because

you might hope to get paid money, one way or another, for saying so

they would only undermine the provision of new lifesaving drugs and devices and would artificially limit provision, and this was true no matter what prices pharma demanded. If the share of national income devoted to health care were to expand inexorably, then that must be what consumers want, because markets work and health care is a commodity like any other. By the time of the pandemic, U.S. health care was absorbing almost a fifth of GDP, more than four times as much as military expenditure, and about three times as much as education. And just in case one might think that health care has anything to do with life expectancy, the OECD currently lists U.S. life expectancy as thirty-fourth out of the forty-nine countries that it tabulates. (That is lower than the figures for China and Costa Rica.)

Unbranded pharma is actually quite cheap in the US. Yet, Americans spend about 250 percent as much as Europeans.

I do not want to make the error of drawing a straight line from a body of thought to actual policy. In his General Theory (1936), Keynes famously wrote that “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

But Keynes was so stupid he thought diminishing returns to global agriculture had set in after the Great War. America was a net food importer. Germany would starve unless it conquered land to its east. Hilter was channelling Keynes's 'Economic consequences' when he invaded Poland.

He added “I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.”

Bad ideas like his own. Don't pay people to dig holes and then fill them in. People will think the lunatics have taken over the asylum. Confidence in the Government would evaporate.

Keynes was wrong about the power of vested interests, at least in the United States, but he was surely right about the academic scribblers. Though the effect works slowly, and usually indirectly. Hayek understood this very well, writing in his Constitution of Liberty (1960) that the direct influence of a philosopher on current affairs may be negligible, but “when his ideas have become common property, through the work of historians and publicists, teachers and writers, and intellectuals generally, they effectively guide developments.”

By 1950, voters in Europe and America had turned their back on Socialist policies and embraced free markets. Hayek wasn't ahead of the curve. He was behind it.

Chicago analysis serves as an important corrective to the naïve view that the business of government is to correct market failures. But it all went too far.

Nobody cares what stupid shite Professors of non-STEM subjects spout.

Friedman was an astonishingly effective rhetorician, perhaps only ever equaled among economists by Keynes.

But Keynes's General Theory only came out after FDR's New Deal was well underway. As he said in his introduction to the German edition, his system would work better in Fascist countries. The plain fact is that Britain should have had a professional cadre of Budget specialists who would have worked out 'multipliers' for different industries. Essentially, the taxman is a partner in enterprises. Sometimes he should put more money in to get more money out. Government is just a service industry.

Politicians today, especially on the right, constantly extol the power of markets.

They also try to make out they are God fearing Christians who are appalled by abortion and pornography and the sort of gay sex they pay a lot of money for.

“Americans have choices,” declared Former Utah congressman Jason Chaffetz in 2017.

Why did he resign? What is a 'mid life crisis'? How much gay sex does it involve?

“Perhaps, instead of getting that new iPhone that they just love, maybe they should invest in their own health care. They’ve got to make those decisions themselves.” Texas Republican Jeb Hensarling, who chaired the House Financial Services Committee from 2013 to 2019, became a politician to “further the cause of the free market” because “free-market economics provided the maximum good to the maximum number.” Hensarling studied economics with once professor and later U.S. Senator Phil Gramm, another passionate and effective advocate for markets. My guess is that most Americans, and even many economists, falsely believe that using prices to correct an imbalance between supply and demand is

how such imbalances are corrected

not just good policy but is guaranteed to make everyone better off.

More particularly, because I can book you a nice mansion in Heaven for the low low price of $9.99. This is actually illegal because the Pope got Congress to put in an inflated minimum retail price which is why you need to send me the money through the dark web.

The belief in markets, and the lack of concern about distribution, runs very deep.

America is a big country with lots of talented people. Things work differently there.

And there are worse defunct scribblers than Friedman. Republican ex-speaker Paul Ryan and ex-Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan

a Nobel laureate like Deaton

are devotees of Ayn Rand, who despised altruism and celebrated greed, who believed that, as was carefully not claimed by Hayek and other more serious philosophers—the rich deserved their wealth and the poor deserved their misery. Andrew Koppelman, in his 2022 study of libertarianism, Burning Down the House, has argued that Rand’s influence has been much larger than commonly recognized.

Americans weren't greedy bastards till a brainy Russian girl told them to be greedy bastards.

Her message that markets are not only efficient and productive but also ethically justified is a terrible poison—which does not prevent this message from being widely believed.

Any yet Deaton produces books which are sold through the market. It seems terrible poisons aren't so terrible if they end up inflating your bank account.

The Chicago School’s libertarian message of non-regulation was catnip to rich businessmen who enthusiastically funded its propagation.

Soros is rich. What's he funding?

They could oppose taxation in the name of freedom:

It was very naughty of the Americans to get rid of mad King George just because they didn't want to pay taxes to him.

the perfect cover for crony capitalists, rent seekers, polluters, and climate deniers.

is what a paranoid nutjob would say. Why not go the extra mile and denounce the Post Office as the perfect cover for a paedophile ring.

Government-subsidized health care as well as public transport and infrastructure were all attacks on liberty.

As was having to pay for killing random Muslims in far away countries.

Successful entrepreneurs founded pro-market think tanks whose conferences and writings amplified the ideas.

Unsuccessful entrepreneurs could not do so. That's so unfair!

Schools for judges were (and are) held in luxury resorts

as opposed to stinky shitholes

to help educate the bench in economic thinking; the schools had no overt political bias, and several distinguished economists taught in them. The (likely correct) belief of the sponsors is that understanding markets will make judges more sympathetic to business interests and will purge any “unprofessionalism” about fairness.

38 American States elect their Supreme Court judges. 37 million dollars was spent on a recent Wisconsin election. Soros spends big on this sort of thing.

Judge Richard Posner, another important figure in Chicago economics, believed that efficiency was just, automatically so—an idea that has spread among the American judiciary.

He was right. Economies of scope and scale should be encouraged. Consumers want lower prices.

In 1959 Stigler wrote that “the professional study of economics makes one politically conservative.” He seems to have been right, at least in America.

In 1959, conservatives in America were for Jim Crow.

There is no area of the economy that has been more seriously damaged by libertarian beliefs than health care.

The US spends about 16 per cent of per capita Income on Health. The UK and other European countries spend about 12 per cent. But US public spending is the highest in the world. Private spending wise, Switzerland is top.

While the government provides health care to the elderly and the poor, and while Obamacare provides subsidies to help pay for insurance, those policies were enacted by buying off the industry and by giving up any chance of price control. In Britain, when Nye Bevan negotiated the establishment of the National Health Service in 1948, he dealt with providers by “[stuffing] their mouths with gold”—but just once.

Sadly, the UK, like the rest of Europe, is going to have increase per capita spending to US levels.

Americans, on the other hand, pay the ransom year upon year.

Big Pharma spends 200 million pounds a year getting NHS trusts and consultants to prescribe more of their stuff.

Arrow had lost the battle against market provision, and the intolerable became the reality. For many Americans, reality became intolerable.

Which is why they are running away to Canada.

Prices of medical goods and services are often twice or more the prices in other countries, and the system makes heavy use of procedures that are better at improving profits than improving health. It is supported by an army of lobbyists—about five for every member of Congress, three of them representing pharma alone. Its main regulator is the FDA, and while I do not believe that the FDA has been captured, the industry and the FDA have a cozy relationship which does nothing to rein in profits. Pharma companies not only charge more in the United States, but, like other tech companies, they transfer their patents and profits to low-tax jurisdictions. I doubt that Smith would argue that the high cost of drugs in the United States, like the cost of apothecaries in his own time, could be attributed to the delicate nature of their work, the trust in which they are held, or that they are the sole physicians to the poor.

I doubt Smith would argue anything because he is dead. The US currently contributes a little less than half of total Pharma R&D. That share will decline as China ramps up but ageing, affluent, populations are going to spend more on health one way or another. Pharma costs may come down but Baumol cost disease is still going to bite you in the ass.

When a fifth of GDP is spent on health care, much else is foregone. Even before the pandemic ballooned expenditures, the threat was clear. In his 2013 book on the 2008 financial crisis, After the Music Stopped, Alan Blinder wrote, “If we can somehow solve the health care cost problem, we will also solve the long-run deficit problem. But if we can’t control health care costs, the long run budget problem is insoluble.”

Unless people top themselves before they get too old.

All of this has dire effects on politics, not just on the economy. Case and I have argued that while out-of-control health care costs are hurting us all, they are wrecking the low-skill labor market and exacerbating the disruptions that are coming from globalization, automation, and deindustrialization. Most working-age Americans get health insurance through their employers. The premiums are much the same for low-paid as for high-paid workers, and so are a much larger share of the wage costs for less-educated workers. Firms have large incentives to get rid of unskilled employees, replacing them with outsourced labor, domestic or global, or with robots. Few large corporations now offer good jobs for less-skilled workers. We see this labor market disaster as one of the most powerful of the forces amplifying deaths of despair among working class Americans—certainly not the only one, but one of the most important.

So, structural changes in the economy cause deaths of despair. Freeze up the economy and though people will still die, theirs will be very cheerful deaths.

According to these accounts, the government is powerless to help its citizens—and in fact, it regularly and inevitably hurts them.

Also the Post Office is just cover for a paedophile ring.

Scotland shows that you do not need an out-of-control health care sector to produce drug overdoses—that deindustrialization and community destruction are important here just as they are in the United States.

Scotland has been invaded by evil Sassenachs. Tory bastids are exterminating entire communities of peaceful crofters.

But Scotland seems to have skipped the middle stages, going straight from deindustrialization and distress to an illegal drug epidemic. As with less-educated Americans, some Scots point to a failure of democracy: of people being ruled by politicians who are not like them, and whom they neither like nor voted for.

What does Deaton point to? Scots are very smart, enterprising, and are committed to Scandinavian style Social Democracy. Sadly, they aren't boring or timid or spiritless. If there are generational problems, on the other hand, then there is a Pareto law such that concentrating resources on breaking such 'cycles of deprivation' will have a disproportionate impact. Apparently there are about 60,000 people with a drug problem of whom about 40 percent are receiving treatment of some kind. But, the most at risk may only be a couple of thousand or so. Anyway, this is the sort of thing Scottish people are better at figuring out for themselves. Hopefully, the SNP will move in a less namby-pamby direction now Sturgeon is history.

The inheritors of the Chicago tradition are alive and well and have brought familiar arguments to the thinking about deaths of despair. As has often been true of libertarian arguments, social problems are largely blamed on the actions of the state. Casey Mulligan, an economist on Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors, argued that by preventing people from drinking in bars and requiring them to drink cheaper store-bought alcohol at home, COVID-19 public health lockdowns were responsible for the explosion of mortality from alcoholic liver disease during the pandemic. Others have argued that drug overdoses were exacerbated by Medicaid drug subsidies, inducing a new kind of “dependence” on the government. In 2018 U.S. Senator Ron Johnson of Wisconsin issued a report, Drugs for Dollars: How Medicaid Helps Fuel the Opioid Epidemic. According to these accounts, the government is powerless to help its citizens—and not only is it capable of hurting them, but it regularly and inevitably does so.

Sadly, Ron Johnson is right. Poorer people had an incentive to get prescriptions and buy drugs very cheaply and then sell them off at a big profit.

I do not want to claim that health care is the only industry that we should worry about. Maha Rafi Atal is writing about Amazon and how, like the East India Company,

which gave the Indian sub-continent better governance than it ever had previously. True, the Crown took it over, but the fact is India has kept and built upon all the institutions created by John Company.

it has arrogated to itself many of the powers of government, especially local government,

John Company was able to turn a profit by getting into the opium trade. Amazon isn't doing that. On the other hand it is true that if I need a police detective to solve a homicide case, I have to go on to the Amazon website.

and that, as Smith predicted, government by merchants—government in the aid of greed—is bad government.

It turned out to be better government than government in the aid of some fanatical religion or degenerate dynasty.

Deaton, it must be said, is honest enough when he handles data. The same can't be said of Amartya Sen, who readily confesses that he knows no econometrics.

The beliefs in market efficiency and the idea that well-being can be measured in money have become second nature to

guys who work for a living

much of the economics profession. Yet it does not have to be this way. Economists working in Britain—Amartya Sen, James Mirrlees, and Anthony Atkinson—pursued a broader program, worrying about poverty and inequality and considering health as a key component of well-being.

Sen claimed that Britain might experience a famine under Thatcher. He was tolerated because he was a darkie. Mirrlees and Atkinson were ignored because Labour had realized that the working class didn't care about equality. They wanted cheap holidays in Franco's Spain.

Sen argues that a key misstep was made not by Friedman but by Hayek’s colleague Lionel Robbins,

a fool who thought 'ordinal' measures were kosher but 'cardinal' measures were not. Sen himself would point out that, thanks to Szpilrajn extension theorem, any ordinal measure could be turned into a cardinal measure. The thing made no difference whatsoever.

whose definition of economics as the study of allocating scarce resources among competing ends narrowed the subject compared with what philosopher Hilary Putnam calls the “reasoned and humane evaluation of social wellbeing that Adam Smith saw as essential to the task of the economist.”

But there were no 'economists'- as opposed to guys getting rich organizing tax-farming schemes for the Government- back then.

Sen, ludicrously, still doesn't get that Smith was saying 'darkies aren't really human beings. Fuck 'em.' He thought Smith lurved niggers. Still, Smith was less dismissive than Hume of middle class British people.

And it was not just Smith, but his successors, too, who were philosophers as well as economists.

They were shit. Nobody gave a toss about them. Those who got rich in new industries got into Parliament and wrote the laws.

Economics should be about understanding the reasons for, and doing away with, the world’s sordidness and joylessness.

No. That is the function of Pop Music and smoking a lot of pot.

Sen contrasts Robbins’s definition with that of Arthur Cecil Pigou, who wrote, “It is not wonder, but rather the social enthusiasm which revolts from the sordidness of mean streets and the joylessness of withered lives, that is the beginning of economic science.”

No. Public Finance was the beginning of economic science. The Government started getting quite good data sets and some mathsy guys could earn a little money, or gain a little influence, by interpreting those statistics and making policy recommendations. By the time Keynes got to Uni, there was a clear route from a supposed proficiency in 'Economics' to the Treasury and thus a position of influence.

Incidentally, a shitty country with little in the way of Public Finance could have lots of guys with Economics degrees as well as more and more 'mean streets' and 'withered lives'. That's what happened to Sen's Calcutta thanks to, first Provincial Autonomy and then Partition and Secular Socialist Democracy.

Economics should be about understanding the reasons for, and doing away with, the world’s sordidness and joylessness. It should be about understanding the political, economic, and social failures behind deaths of despair.

We have plenty of Netflix series about how the oxycontin epidemic occurred. But it would be foolish to suggest that the underlying reason is that some silly Professor, or bunch of Professors, chose the wrong methodology a hundred years ago. Deaton forgets that there were plenty of Marxist economists. But they were wholly mischievous. Still, it is true that you shouldn't do anything which is fun. You must dedicate your life to be as boring as possible. If this involves telling stupid, virtue signalling, lies- so be it.

But that is not how it worked out in the United States.

Econ PhDs of a mathsy type can get you a well enough paid with Bezos. Americans think going to Uni should be about earning more money not understanding the reasons for doing away with Gravity or Joylessness or other things which are a total bummer, dude.

No comments:

Post a Comment