Prof Steve Keen, on Substack, asks-

Why are Economists Trying to Hide the Simplest Equation in Economics?

Steve Keen

May 18, 2024

Sadly, equations in Econ are examples of the 'intensional fallacy'. In other words, the 'intensions' involved don't have well-defined extensions because they are epistemic and impredicative. Thus there are no sets and no graphs of functions. There is mere hand waving.

BTW, even tautologies are false where the intensional fallacy raises its ugly head. Why? Leibniz's law of identity is violated. X is not equal to X if X does not have a well defined extension.

Galbraith once remarked that “The process by which banks create money

they don't. They lend money or extend credit. A lot of the time, credit is just as good as money but, sadly, it isn't money- i.e. legal tender. That's why, in 1991, my neighbour couldn't pay his taxes with a check drawn on his bank even though he had adequate funds there. This was because the Bank of England had shut it down. He had deposit insurance and thus did get his money back after some time. But, in the short run, that made no difference. He had to borrow cash from friends to pay his taxes and thus avoid prosecution.

is so simple that the mind is repelled. Where something so important is involved, a deeper mystery seems only decent” (Galbraith 1975, p. 22).

The only mystery here is why a Professor of Economics says 'banks create money' when what they do is called 'credit creation'.

He was right on the first count. Banks operate according to the rules of double-entry bookkeeping,

No. They are in the business of lending money at a higher rate of interest than they offer depositors. Like other businesses, they employ Accountants who keep track of transactions but don't know whether 'equity' will rise or fall over the quarter. It is only at the 'Trial Balance' stage that decisions are made as to whether to show equity as having increased or decreased. The Accountant may counsel prudence and suggest that greater provision should be made for write downs or with respect to contingent liabilities.

the key rules of which are (a) to record all financial transactions twice, once as a debit (DR) and once as a credit (CR);

That is the journal entry. But it isn't set in stone. At the trial balance stage, adjustments are made. There are write-downs or a booking of profits.

and (b) to ensure that the record of every transaction follows the rule that Assets minus Liabilities Equals Equity.

But we don't know whether a transaction will produce income (e.g. a loan to a guy who pays interest promptly) or whether it will lead to a write-off (i.e. a decrease in the Bank's equity).

Take the statement by the Bank of England that “bank lending creates deposits”

i.e. modern banks create a deposit in the name of the borrower equal to the loan being granted. However, this isn't always the case. The borrower may not, for legal reasons, be permitted to have a deposit with the lending bank. Here a dummy account is created.

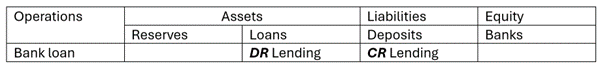

Put into a double-entry bookkeeping table, this is as shown in Table 1:

Table 1: The double-entry bookkeeping for the Bank of England's statement

The rules about when you record something as a Debit (DR) or a Credit (CR) are quite confusing,

Not if you are an accountant. When doing your trial balance, you have to reverse some of your Journal postings because things didn't turn out the way your enterprise had hoped. Why? Well, your customers had the same problem. They expected one outcome but got another. Ex ante isn't ex poste. It is at the trial balance stage that this becomes clear.

but there’s another way to record this: use a plus key for anything that increases an account, and a minus for anything that decreases it, and make sure that the equation “Assets-Liabiities-Equity equals Zero” is obeyed.

We don't know for sure what will increase or decrease the balance on any account. Thus all three items in the equation are unknown.

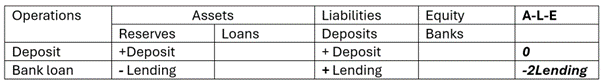

That is shown in Table 2.

Share

Table 2: Bank lending using + and - rather than DR and CR

This may be fine for Cash flow statements but you do need to work out the Profit & Loss before doing your Trial Balance. In practice, you may fudge things and book notional profits so as to show no decline in equity. But, will your auditors let you get away with it?

The equation describing this process is simply the translation of the Bank’s English into the formal language of mathematics. The verbal expression is “The rate of change of Deposits equals Lending”.

This is sheer nonsense. The rate of change of a thing may be related to the rate of change of another thing. It can't be equal to the thing itself. Suppose Deposits rise by ten percent; will new Loans equal one tenth of total Deposits? No. Don't be silly. Deposits may go up because everybody is putting money in the bank. Nobody is borrowing to spend.

In the symbols of mathematics, the “fraction” d/dt stands for “the rate of change of”, and the equals sign “=” for “equals”. This equation then is the mathematical form of the Bank of England’s declaration that “bank lending creates deposits”:

d/dt Deposits = Lending

This is clearly false. Deposits can rise when nobody is borrowing.

Notice that there is no role for Reserves in that equation.

Notice the equation is utter shit.

That, according to mainstream economists, is the problem, because they have been teaching for decades that Reserves play an essential role in bank lending.

Banks know, from long experience, that most inter-bank transactions (e.g. my writing a check to a guy who banks with a different bank) net out such that only a very small percentage of total transactions give rise to flows of money. But this is also the reason most businesses have very little cash relative to the volume of business they do.

In what they call “Fractional-Reserve Banking”, banks are supposed to take in deposits by the public, hang onto part of that as Reserves, and then lend out the rest.

No. It is simply an empirical observation that well run banks will 'net out' the vast majority of transactions. Actual cash flows between them will be small. A badly run bank- one which lends to losers- will find there is a continuous net outflow of cash. It needs to get a fresh infusion of equity and reform its lending practices.

But the same thing is true of a brokerage or market-maker. Indeed, any company with a cash flow problem will have its credit downgraded. Why? The Expectation is that it will go to the wall unless it changes its ways. Credit is just another word for 'belief', 'faith' or 'expectation'.

This is how the popular textbook by Mankiw puts it:

Kids read textbooks. Once you start working for a living, you are expected to show some basic common sense.

Eventually, the bankers at First National Bank may start to reconsider their policy of 100-percent-reserve banking.

Fuck off. Banking evolved out of business enterprises with certain types of economies of scope & scale which noticed that cash in hand falls in proportion to volume of transactions. Why? People trust you. Also, they are using your IOUs. You can make a bit of money by doing the 'netting out' yourself.

Leaving all that money idle in their vaults seems unnecessary. Why not lend some of it out and earn a profit by charging interest on the loans?... if the flow of new deposits is roughly the same as the flow of withdrawals, First National needs to keep only a fraction of its deposits in reserve. Thus, First National adopts a system called fractional-reserve banking. (Mankiw 2016, p. 332)

This is a 'just-so' story. It is something you tell kids. The moment you start working you realize that empirical regularities are what business models are based on. Moreover, the thing is 'Muth rational'- i.e. everybody understands why the empirical regularity works most of the time and why and when it can break down. This is why there will be a market for 'money at call'. What was helpful for Western economies was the Government creating 'riskless assets'- gilts, Treasury Bills etc- which was helpful for portfolio choice and the emergence of sophisticated financial markets.

Trying to put “fractional reserve banking” into double-entry bookkeeping terms causes immediate problems.

Nobody knows how much cash in hand you will have on a specific day. 'Fractional reserve banking' is merely an empirical regularity which fluctuates. It doesn't drive decisions. You don't say 'our reserves are up- lend more!'. You say 'lend more if you get good quality loan applications'. That's your core business. If you are successful in it, you can get liquid assets quite cheaply.

If you try to show the loan increasing Deposits,

a loan increases deposits and is shown as doing s in the Journal

then you violate the rules of accounting: the row does not sum to zero, as it should.

Yes it does. You have an asset- viz. the loan- and an equal and opposite liability- viz. the deposit upon which the borrower can draw on. (Actually, you are also posting a revenue item (interest & fees owed) and an expenses and a profit item. But if the loan ceases to perform, you will have to reverse some of those items.

Table 3: The obvious accounting error in the Fractional Reserve Lending model

The line also shows the borrower getting the money—the Deposit account increases—but there’s no debt recorded by the bank against the borrower’s account. There must be a missing step here.

There is a loan account. It is the corresponding asset.

And there is, but you won’t see this explained in any mainstream economics textbook,

because guys who teach economics live in a fantasy world.

because they don’t really care about money: the whole point of mainstream models of money is to justify not including banks, and debt, and money in macroeconomic models.

The only point of macro models is making good- or useful- predictions. Nobody cares how the sausage is made.

Once they have that excuse—even if it’s a bad one—then they can persist with their preferred model of capitalism as a barter system, in which money plays no essential role.

That's not the problem. It is that Knightian Uncertainty (the fact that we don't know all possible future states of the world or what probability is associated with them) is neglected. Only if it didn't exist could 'Accounting identities' constrain decision making. It is easy to make fun of the 'just so' stories Econ students are traditionally told. But this dude is saying something infinitely stupider and more mischievous.

It also suits their anti-government ideology. There are two control mechanisms in the model of “Fractional Reserve Banking”, both of which are under the control of the government: the creation of Reserves, and the fraction that banks are required to hang onto of any deposit.

Very true. If the Govt. says 'you need only hold 0.0001 percent in liquid assets, then the Banks will go around lending millions to hobos. It won't occur to them that a hobo aint going to repay a loan. The thing simply won't be profitable.

If there’s too much money—and therefore inflation—it’s the government’s fault;

Yes. Government's issue fiat currency. If they flood the market with currency, it will lose value- i.e. prices go up.

if there’s too little money—and therefore deflation—it’s the government’s fault.

It may be. It may not. There is such a thing as a liquidity trap- i.e. people just hold extra money. They don't spend or invest it.

The private banking sector gets off scot-free.

It either makes a profit or goes bankrupt or gets disintermediated.

That is the real reason that they’re trying to hide this simple “bank lending creates deposits” equation, whether they’re aware of it or not. If you take this equation seriously, then you have to include banks, and debt, and money, in macroeconomic models.

To my certain knowledge, in the UK, macro models have had M3 since 1973. That was more than 50 years ago.

Neoclassicals leave all three of them out, and yet purport to be modelling capitalism.

The missing steps in “Fractional Reserve Banking”

I took the standard Econometrics course at the LSE in 1980-81. It was fucking obvious that the 'fraction' was variable. Indeed, money was becoming more Kaldorian- i.e. endogenous- because of Goodhart's law which was propounded in 1975.

If they took money seriously, they’d notice the flaw in Table 3 and realise that two amendments were necessary: firstly, to make the line obey the Laws of Accounting, falling Reserves can be paired with rising Loans. Secondly, for the borrower to actually get any money, the loan must be in cash (or some other negotiable instrument): the borrower has to receive cash in return for accepting the liability of the loan from the Bank.

Why? I get a home improvement loan and write checks to the builder on that account. It keeps things simple for me.

Table 4: The Banking Sector's view of Fractional Reserve Banking done properly

Table 5: The private non-banking sector's view of Fractional Reserve Banking done properly

So at least two tables are needed to show the process fully (Table 4 and Table 5), whereas one was enough for the real-world process shown in Table 1. Then the model works, and the equation gives Reserves a necessary role in lending.

They have no role. There is an empirical regularity but it fluctuates. This is related to the velocity of circulation which varies seasonally.

There’s just one problem: when was the last time you (or anyone else) got a loan in cash? That’s the province of loan sharks these days, not banks, who directly credit the account of the borrower when they make a loan—or they credit the account of a merchant when you swipe your credit card to buy something at a shop.

What they’re leaving out

What this cretin is leaving out is the fact that there is a fucking loan account which is the Bank's asset and the borrower's liability.

By omitting banks, private debt and money from macroeconomics, Neoclassical economists are leaving out of their analysis the main factors that cause booms and busts in a capitalist economy.

Leave out Knightian Uncertainty and you have a Society where there is no need for language or education or scientific research. All information is encoded in the Arrow-Debreu price vector. You know the day and time of your death as well as the birthday of your distant descendant in the 31st century. Naturally, you can't explain anything in the real world if you assume we live in fairy-land.

You might think that describing capitalism’s cycles accurately might be of some importance to Neoclassical economists. And it is, but only so long as the explanation fits within their paradigm. Part of that paradigm is that money doesn’t have what they call “real” effects—by which they mean cause changes in factors like GDP and employment.

Nonsense! Pigouvian 'real-balance' effects are perfectly Neo-Classical. Maybe this dude means 'super-neutrality' or some such shite. But nobody making money in the field bothers with shite like that.

So they ignore data like that shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, which are copied from my post “Why Credit Money Matters” (posted here on Patreon and here on Substack). Ultimately, they’ll ignore the Great Recession/Global Financial Crisis, the same way they ignored the Great Depression.

If you like my work, please enable me to continue doing it by supporting me for as little as $1 a month (or $10 a year) on Patreon, or $5 a month on Substack.

This isn't work. It is a wank. The odd thing is Australian economists tend to be smart. Maybe this whole thing is some elaborate practical joke.

No comments:

Post a Comment