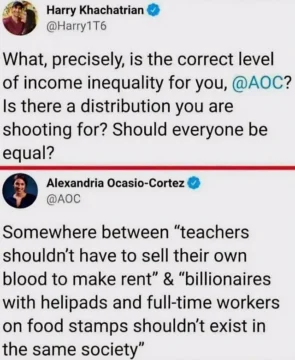

Range egalitarianism is the notion people should not be concerned with the exact level of equality, but rather with keeping inequality within a certain acceptable range. The problem is that nobody can say what that range should be at any give moment. Maybe, the current global 'fitness landscape' requires more inequality- e.g. Elon Musk having trillions of dollars so that he can invest it new technologies which ordinary people know nothing about- or less inequality (otherwise, what is to stop people quitting work and getting a Doctor's note saying they are too sick to work? This means we have to import labour. But that, by itself, could lead to a political backlash against 'demographic replacement'.)

Tim Sommers has an essay in 3 Quarks on this issue.

Range Egalitarianism

by Tim Sommers

Rents may be too high in some places. Those on average incomes may have to move away from there. That may not be a bad thing in itself. Chances are, their quality of life will improve. Maybe families will move out of areas where there aren't enough teachers. But their children may benefit from growing up in a less congested environment.

We could get rid of billionaires. But what if they move to places where they pay less in tax and have more opportunities to invest in new high-tec industries? Our tax revenue will fall. We will fall behind in the new industries. Other countries may be able to dictate terms to us because they control the vital new technology. They can 'sanction' us if we don't comply with their demands.

The economy is not a force of nature. We have some control over it.

We can screw it up. But we can also screw up our environment.

Granted, it’s also not like a machine controlled directly by levers, switches, and buttons either. But when the state acts, intentionally or not, it often influences the distribution of income and wealth.

The State can encourage investment and 'R&D' in new technology. But it can also raise taxes and thus cause a 'brain drain' and 'capital flight'.

More often than not, it influences the distribution of wealth and income in reasonably predictable ways.

Sadly, this is not the case. There are 'unintended consequences'. If factor elasticity is high, policy interventions may be self-defeating.

It seems to me that, for this reason alone, we should care what the ideal distribution of wealth should be.

Why should I care about the ideal theory of Physics? I am too stupid to understand that subject. There were philosophers who thought that they could say, on a priori grounds, what was good or bad Physics. But they all turned out to be wrong. Ideals are misleading. Idealism, as a philosophical project, crashed and burned long ago. Kant thought he knew why Newton must be right. But Newton was wrong.

The ideal distribution is, at a minimum, one factor we have an ethical obligation to take into account in governing.

This is like the claim that Philosophers could arrive at a priori synthetic judgments which must be true. Sadly, no such judgments exist.

Some people say that any ideal distribution is unrealistic, impossible to achieve.

Others say that talk of this type is a vacuous type of virtue signalling. They are right.

That’s alright though. Ideals – perfectionism, utilitarianism, the Ten Commandments – are, as they say, honored as much in their breach. We should still have ideals to follow.

There is nothing wrong with obeying or honouring imperative statements- e.g. 'Be nice! Don't be nasty!' But they have no alethic content. Sometimes, being nice involves doing things others find nasty- e.g. my teechur telling me I should stop studying Math. The answer to 2 plus 2 isn't 'Pizza'. I should quit Collidge & try to get training in mopping floors.

Others say that trying to enforce any particular distribution – equality, first and foremost – leads to coercion and political oppression.

It may do. Alternatively, smart people may simply run away.

I think they say this mostly because they have frightening real-world cases in mind. But people also do terrible things in pursuit of freedom, justice, or whatever.

Some crazy people who seize power may do so. But the reason they are doing so is in order to have even greater power and impunity.

You certainly can pursue equality in a repressive way. Say, seize everyone’s property,

and keep it.

redistribute it,

Don't redistribute it. Those who get it will have countervailing power over you.

and redo that every so often to maintain equality.

The guys who were with you when you gave them property, may try to kill you if you show signs of taking it away.

But you could also, as I implied above, mostly regard equality (or whatever the correct principle is) as a kind of tie-breaker.

Two kids are quarrelling over who gets to play with a toy. As a 'tie-breaker', Mummy says that if they can't agree then she will donate the toy to Goodwill. The kids become quiet. They agree to take turns playing with the toy.

For example, the point of health care is not the distribution or redistribution of wealth per se, but when you must decide between two approaches one of which takes you closer, the other further away, from the ideal distribution, there’s nothing repressive about going with the one that also has a positive effect on the distribution of wealth and income.

Sadly, this may backfire. If people feel healthcare will go disproportionately to the poor refugee, they may support politicians who dismantle the Public Health system.

In other words, there is nothing inherently oppressive about pursuing more distributive equality. It just depends on how you do it.

You have to be strong to actually oppress people. If you are weak you can talk bollocks but everybody will ignore you.

Some people (libertarians, for example) believe that people deserve whatever they can obtain from fair or just initial aquations and/or just transfers – where neither the acquisitions nor the transfers involve force, fraud, or theft. Where these are unjust, the state should act to rectify the situation, but at no point does it rely on the distribution of wealth to decide anything.

Speaking generally, this is a justiciable matter- i.e. one resolved by courts of law. Unconscionable contracts may be struck down. If there is a gap in the law, the Legislature may pass a law and set up an Enforcement Agency.

One problem with this view is that the current distribution of wealth is largely the result of force, fraud, or theft.

Nonsense! It is largely the result of some people having really smart parents or grandparents. Also, if you do stupid shit, chances are you end up poor.

Robert Nozick, plausibly the most influential libertarian of them all, surprisingly suggests that solution (at least sometimes) is to follow John Rawls’ preferred distributive principle – the least well-off should be as well-off as possible.

The least well-off are dying or close to death. In any case, nobody knows who is worst-off. Bernie Madoff's investors thought they were well-off. They weren't.

A more serious problem for libertarians is that it is not clear that one can even define just acquisition or transfers without resorting to distributive claims at some point. John Locke

who lived at a time when Englishmen could go off to the New World and create any type of Society they liked.

and Nozick both say just acquisitions involve “mixing your labor” with something, but then say it is limited in that you must “leave enough and as good for others.”

the native Americans?

Isn’t that a distributive principle?

It is meaningless. Still when helping yourself to cake, it is polite to leave enough for the next guy.

Or consider property rights. Not the version of property rights that philosophers often focus on, because it doesn’t seem crazy, at least about these sorts of property rights, to say they are “natural” rights.

Sadly, those who spoke of 'natural rights' didn't think Native Americans had any.

Consider zoning law instead. It involves property rights, but zoning law doesn’t seem like it can be derived from natural laws.

It is derived from a 'collective action problem'. Everybody wants to live in a nice residential neighbourhood. But they may also have an incentive to get lots of money by setting up a drug den or brothel in the basement.

Zoning and rezoning creates or addresses various problems, creates or forecloses various opportunities, and it also impacts the distribution of wealth.

It affects property values- i.e. wealth. It may not change the distribution of it.

It seems arbitrary to me to say that you should never take the distributive impact of zoning into account.

Unless you are a Town Planner, you should only focus on how you are personally affected. Will the value of your property rise or fall? What about your quality of life? You may have to trade-off the one against the other.

So, far I have argued that even if distributive justice it is an ideal that we will never fully achieve, it’s still worth trying to figure out what it is.

In mathematics, there are 'existence' proofs. However, if we also have a proof that the thing is not effectively computable, we ought not to waste time trying to figure out what it might be. Since there is a mathematical representation of the economy, we know that it is futile to try to figure out things which are not effectively computable.

I argued that there is nothing inherently repressive about attempting to achieve a just distribution.

But, it is inherently stupid. The thing may exist but is not effectively computable.

And that focusing only on rights to obtain or transfer property to avoid distributive questions is probably not workable.

Yet courts in affluent countries work well enough. The problem is always with the cost of enforcement. In practice, this means the Social Contract is 'incomplete'. There is wriggle room. Control rights aren't perfectly aligned with beneficial rights.

We are likely to fall back onto questions about the fairness of various possible distributions.

Only if we don't understand that problems of concurrency, computability, complexity and categoricity render the thing a complete waste of time.

So, what is the ideal distribution of wealth and income?

Nice people get plenty of people. Nasty people starve to death.

In a Kindergarten everybody gets an equal share.

But the mean kid may knock you down and steal your lunch. That's why I gave up teaching.

Our first thought is probably to distribute the coconut on the desert island on which we are stranded equally. Equality is the default distributive principle in many contexts.

In the short run- yes. We think we will be rescued soon. But the longer we remain on the island, the more likely it is that coconuts will be distributed according to 'Shapley values'. Those who are more productive and who have a higher threat point get more.

Funny thing about equality, you can always make things more equal, reduce the amount of inequality, by just taking stuff away from the well-off – even if you don’t give it to anybody.

They may kill you.

You can always get closer to equality by taking stuff away – which makes some people worse off – even if you don’t give it to someone else (who would then be better off). In other words, equality tells us to sometimes prefer situations were some are worse off and none or better off relative to the status quo. This is called the leveling-down problem. Many philosophers take it to indicate that equality, in an of itself, is not what people care about. What do they care about? Maybe, poverty, immiseration, the plight of the worst-off?

No. They care about their own material standard of living and then have some sort of kin selective altruism linked to reproductive success for those of their own lineage. But, because of radical interdependence, (your distant descendants may marry the distant descendants of people you are not currently related to) this may broaden to include everybody.

Rawls argued for the “difference principle,” which says that inequalities are only justified if they also work to the advantage of the least well-off.

He was wrong. He didn't understand that the way to deal with uncertainty as to your future status (you may be hit by a bus tomorrow) is to go in for 'risk pooling'- i.e. you hedge or buy insurance.

This is called prioritarianism since it gives distributive priority to the worst off.

This is called stupidity. I buy fire insurance just in case my house burns down. I don't support a law saying all those whose houses burn down will get a big sum of money. Why? Careless people benefit. Cautious people suffer. There is 'moral hazard'. Moreover, the fire insurance company has an incentive to push for better provision of Fire Fighting services as well as for changes in building codes to reduce the risk of fire.

Rawls argues for absolute priority. But this seems to create a nested leveling-down problem. For example, if there were a policy that would increase middle-class wages, but from which no benefit at all would go to the least well-off, it violates the difference principle.

People dying of old age get no direct benefit from spending on kindergartens. Thus, no money should be spent on kiddies. The least well-off are very old. Their existence is quite miserable.

Here’s a different way to deal with the least well-off. Why not say that everyone is entitled to a sufficient amount of income and wealth to avoid poverty and have enough to lead a decent life?

Why not say 'It is nice to be nice. Be nice. Don't be nasty.'?

Call this sufficientarianism. One issue is how to set the sufficiency level. What is the minimum?

Unemployment benefit. Should this be turned into 'Basic Income'. No. There will be a disincentive to work.

Also, it’s exclusive focus on the less well-off means it ignores another possible concern about inequality.

Limitarianism argue that no one should have more than a certain amount. “No billionaires,” for example. They argue that democracy and liberty are impossible in a society with too much inequality. One problem limitarians share with sufficientarians, however, is how to set a threshold. How much is too much?

The problem is not that nonsense can be talked. The problem is that if shitheads take over, smart people run away. The State goes off a fiscal cliff.

If we combine these two views, we get a promising distributive approach that we might call sufficiency limitarianism. No one should have too little or too much. But this doesn’t solve the issue of how to set a threshold.

Any cretin can set any threshold. Try to implement it and the State goes off a fiscal cliff.

Consider this. What if people don’t care about things being as equal as possible, but only about avoiding things being too unequal.

In that case, such people run away from America. They become subsistence farmers in underdeveloped countries.

The distribution within a certain range would be a matter of indifference, but falling below or exceeding the range would be considered problematic.

This is the view that I have come to. I call it range egalitarianism. Empirical research suggests that most Americans believe that

they have been anally probed by aliens in flying saucers?

there is too much inequality, but that some level of inequality is morally fine. Most Americans are range egalitarians, then.

That's why Trump won the popular vote- right?

It is a response, again, to the idea that you don’t have to love equality as such, to fear inequality that leaves some unable to meet their basic needs and others with the power to bend the rest of us to their will.

Americans don't just care about Equality. They also support Diversity. That is why Kamala Harris is POTUS.

_________________________________

Appendix: Nozick on Rawls

“Assuming (I) that victims of injustice generally do worse than they otherwise would and (2) that those from the least well-off group in the society have the highest probabilities of being the (descendants of) victims of the most serious injustice who are owed compensation by those who benefited from the injustices (assumed to be those better off, though sometimes the perpetrators will be others in the worst-off group),

i.e. African Americans and First Nation people. Should they be given reparations? The problem is that a lot of White Americans are descendants of poor immigrants who worked in sweat-shops or coal mines etc.

then a rough rule of thumb for rectifying injustices might seem to be the following: organize society so as to maximize the position of whatever group ends up least well-off in the society.”

The least well-off have the strongest incentive to rise in 'general purpose productivity. Raise factor mobility and elasticity (this means high 'transfer earnings'- i.e. workers can easily switch to just as well paid jobs in other industries). This raises total factor productivity and thus increases GNP and Tax Revenue. This in turn means a better welfare 'safety net' can be provided. But this, by itself, reduces risk aversion and thus raises factor mobility and elasticity. It is a virtuous circle.

In the late Sixties, many politicians believed voters cared about equality. Harold Wilson's Government in the UK increased labour's share of National Income to 83 percent. But, it had to devalue the currency. The working class rebelled against having to pay more for their holidays in Franco's Spain. They voted for the Conservative party. Over the course of the Seventies, even the Scandinavians came to understand that the working class didn't like 'solidarity wages'. They didn't care about inequality. They wanted a higher material standard of living in absolute terms. Mitterrand, becoming President with Communist support had to do a U turn and support more free-market policies. But China was more thorough-going in embracing the Market. Equality simply didn't matter- save to some brain-dead academics regurgitating the warmed up sick of the Seventies.

No comments:

Post a Comment